Nollywood veterans and other stakeholders in the movie industry have advocated that the Nigerian film industry should be celebrated for its uniqueness in terms of storytelling, talents and production circumstances and that a better structure should be put in place.

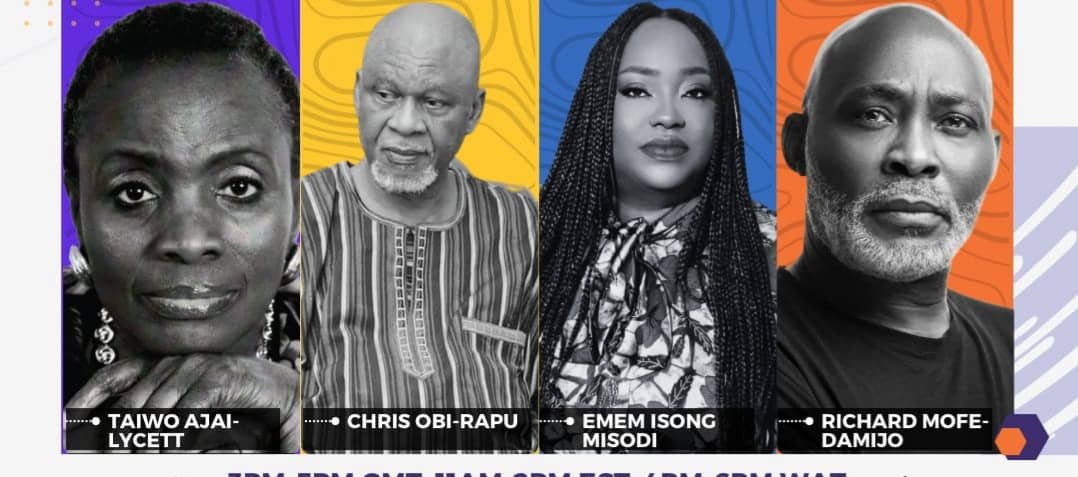

Before an audience of 74 Nollywood stakeholders and others drawn from Africa, UK and the U.S, Ucheyamere Nkwam-Uwaoma and Rejoice Abutsa of Bournemouth University and Cornell University respectively explored the fundamental questions about the film industry’s origin and its global significance. This exploration unfolded in a virtual panel session titled ‘Nollywood Global Circuits,’ featuring prominent Nollywood veterans such as Taiwo Ajai-Lycett, Chris Obi Rapu, Richard Mofe-Damijo(RMD), and Emem Isong, who shared their concerns about the industry.

Filmmaking academics of Bournemouth University, Dr. Samantha Iwowo and Dr. Szilvia Ruszev set the stage for the conversation with their opening remarks. Notably Ruszev, who outlined her fourfold understanding of Nollywood, encompassing Hollywood, European art film, decolonisation, and indigenous filmmaking.

“From my perspective, the question was the positioning of Nollywood cinema, so it struck me that the conversation started with the demand that Nollywood be seen as a cinema in its full right and values not against other cinemas but in its uniqueness in terms of storytelling, talents and production circumstances,” she said.

Mofe-Damijo addressed the constant validation of Nollywood through a Western lens, asserting that its global status results from practitioners’ hard work, pushing creative boundaries, and telling authentic stories.

“The fact that the definition of what cinema is by some Europeans doesn’t particularly accommodate how we make films in Nollywood does not in any way diminish the work that we have,” he said.

RMD expressed his satisfaction that Nollywood has not conformed to European or American aesthetics. “What we have done is to be global as global as we can be using the democratisation of the space by technology to compete with cinema-making cultures where budgets are perhaps the most important thing whereas, for us, it is about telling the story, no matter how limited we are in budget, or how much budget we have, which we have demonstrated through ‘Black Book.’”

Isong highlighted the substantial progress made with diverse voices and representations in the industry today. While deeming the comparison between Hollywood and Nollywood unfair, she acknowledged Nollywood’s efforts, signaling room for improvement.

Veteran actress, Ajai-Lycett, tasked that Nollywood needs to be unionised to get certain structures in place. She advocated for managerial talents for actors to avoid social media controversies which often lead to ridicule. Ajai-Lycett passionately urged for the industry’s recognition as a pivotal force for economic and national development. Additionally, she critiqued the extravagant lifestyles of young actresses, encouraging a shift toward investing more in education than aesthetics.

The session highlight was Rapu’s proposal to rename Nollywood to ‘Naija Cinema,’ emphasising that its current name has become a subject of mockery among academics.

“I’m suggesting that we change the name to something that reflects our identity such as Naija Cinema. Nollywood has become a national cinema because it has been able to meet all the requirements that you can see in any top national cinema either in the US, France or Britain. Nollywood has surpassed it, that by now, almost about a billion people watch it every day globally.”

Rapu’s fellow panelists are however indifferent to the name as long as the industry works speak for itself.

While practitioners debated remuneration, with Isong highlighting the livelihoods of many, Mofe-Damijo stressed the fulfilment derived from passion over pay. As one who has been on many Netflix productions, Mofe-Damijo dispelled claims about streaming platforms dictating storytelling, encouraging acceptance of the industry’s generational shift and its independence.

This echoed the position of Iwowo, who noted in her opening remark that Nollywood, through its inaugural film, ‘Living in Bondage,’ set in motion a movement, “conscious and unconscious, to sustainably demystify the hegemonic budgetary implications of filmmaking and to do this it maximised its affordances like minimalist budgets, human resources, and the power of the consciousness of community in African societies expressible as Ubuntu as well as the tenacity of youths and topical subject matters.”

How this movement continues to shape the global outlook of the industry in the future like the veterans posited depends on the industry’s commitment to put the right structures in place.